From their early days as advertising mediums for businesses to their rising popularity as collectible items among consumers, matchbooks have been playing an important role in American culture for over a century. Although their use has declined significantly in past years, these little, paperboard folders containing match stems are still a ubiquitous part of our collective history and continue to be valued by collectors and enthusiasts alike.

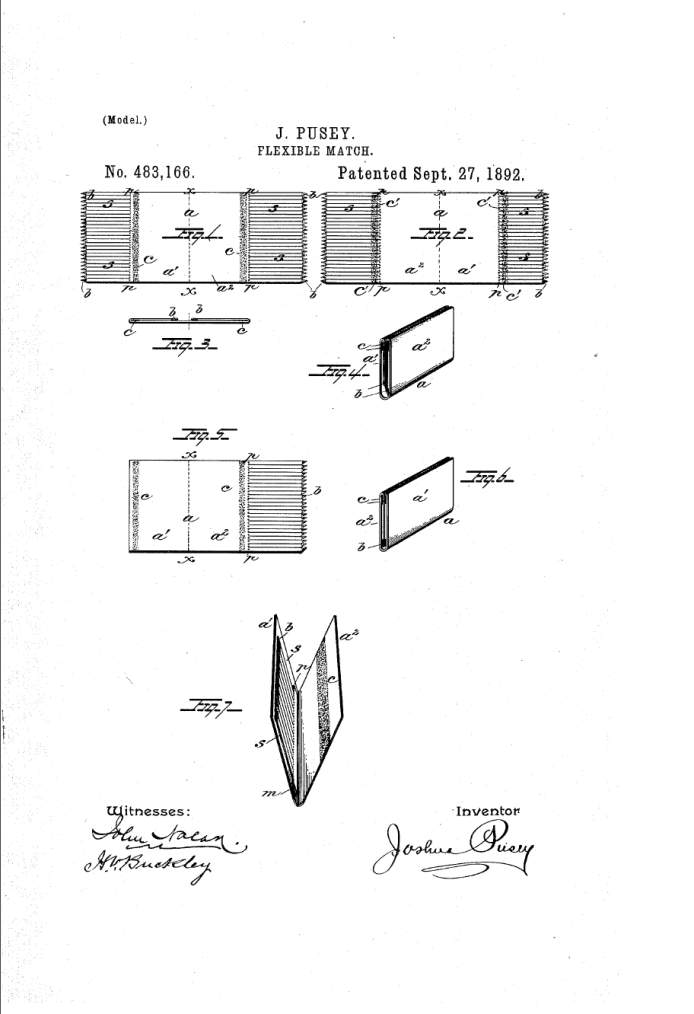

The history of matchbooks—also known as match covers or matchbook covers—can be traced back to the late 1800s, when Joshua Pusey, a Philadelphia patent attorney, first secured a patent on his matchbook design in 1892. Pusey was tired of carrying around a bulky box of matches with him everywhere he went, so he came up with the idea of a tiny, booklet of paper matches that could be easily carried in a pocket or purse. His contraption consisted of two comb-like rows of matches fastened inside a small square of folded paperboard and a strip that could be struck against a rough surface to ignite the matches. Pusey’s design was simple but clever, with one caveat: the coarse striking surface on his design was also put inside the fold, right alongside the matches, and a quick swipe of a match could catch the whole book on fire.

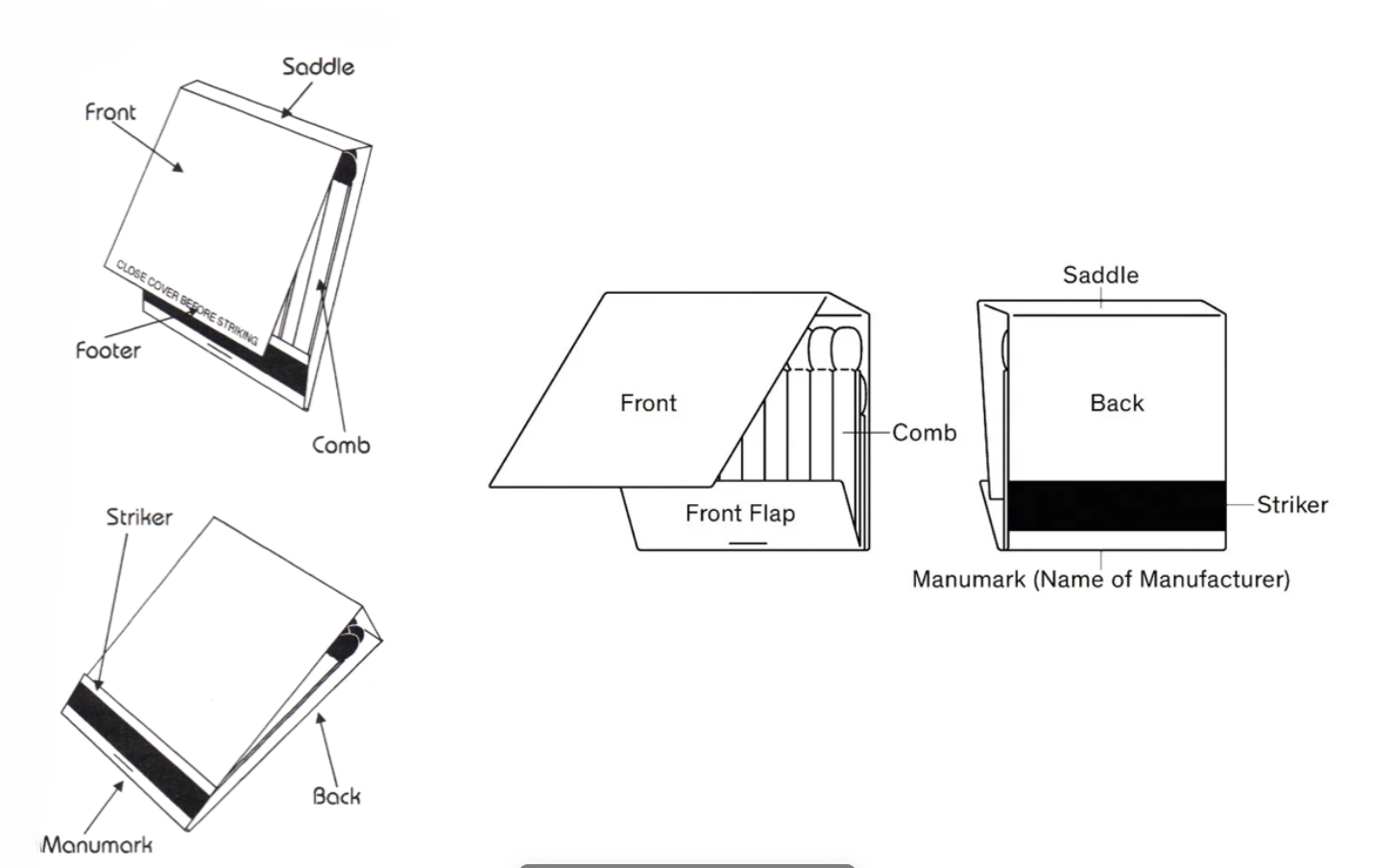

Despite this flaw, Pusey’s invention was deemed illustrious and cutting-edge, but it was only a few weeks later that a Pennsylvania entrepreneur and newspaper proprietor named Charles Bowman developed the first modern matchbook that we know today. What essentially sets apart Bowman’s matchbook design from that of his rival Pusey is that the striker sits on the exterior surface of the match cover instead of being nestled on the interior next to the matches. We also owe to Bowman the eventual creation of the famous catchphrase close cover before striking that was placed on top of every matchbook cover for safety reasons.

In 1893, Pusey challenged Bowman’s patent but he failed to overturn his design, and it was upheld in a decision in March of 1894. Both inventors eventually sold their patents to the Diamond Match Company, one of the best match manufacturers at the time. Pusey let his go in 1896, before securing a job with Diamond itself in their legal department, while Bowman’s design also sold in 1896 after his company—the American Safety Head Match Company—ultimately shut down after three years of operation. Diamond Match Co. came to adapt Bowman’s design into their product, becoming the first mass-producer of paper matchbooks.

US Patent No. 483,166, Joshua Pusey’s matchbook design

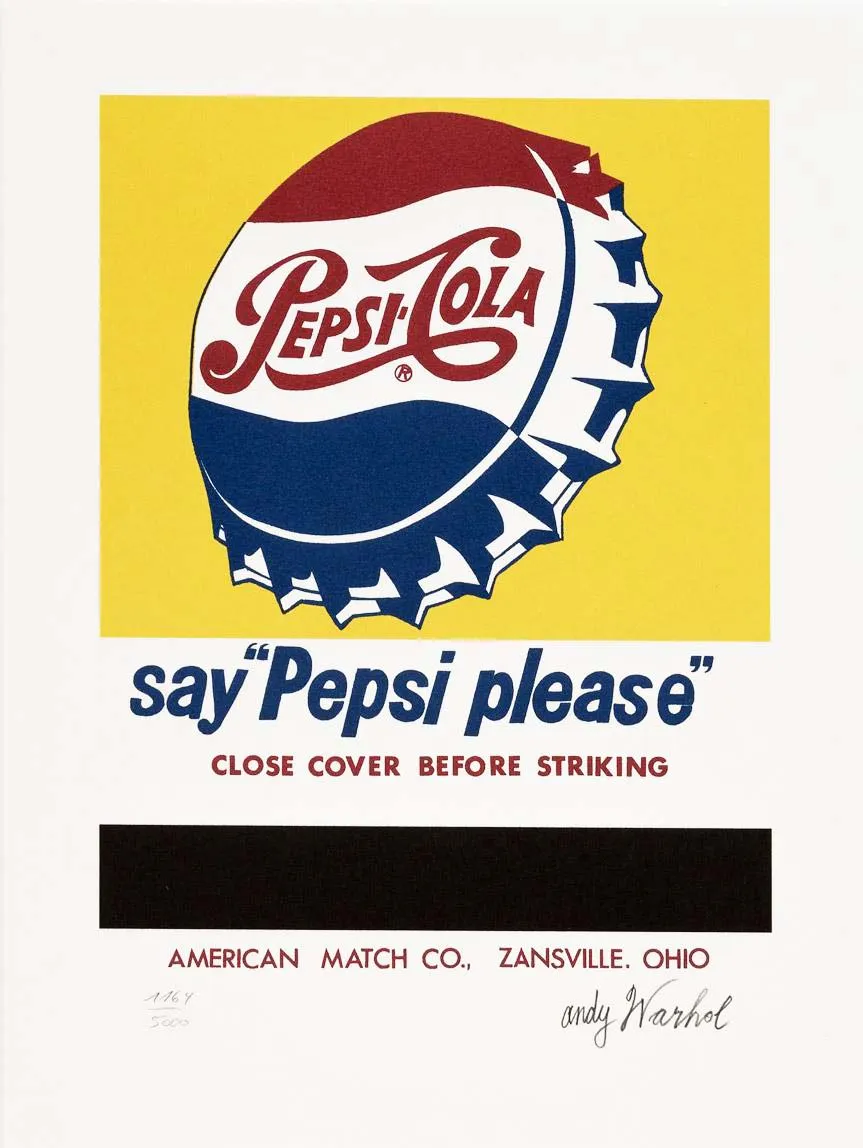

Andy Warhol, Say "Pepsi Please," 1962, CLOSE COVER BEFORE STRIKING

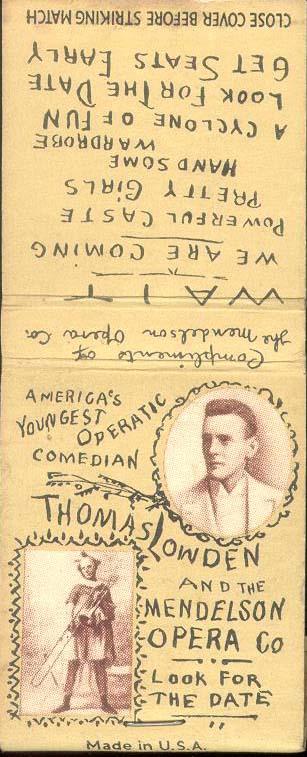

The first commercially produced matchbooks were introduced in the United States in the early 1900s, after the Mendelson Opera Company used blank matchbook covers to handwrite promotional information on the imminent arrival of “America’s Youngest Operatic Comedian,” Thomas Lowden, in 1889. In 1894, inspired by the Opera’s innovation, Diamond Match salesman Henry Traute began approaching manufacturers to promote their products on his company’s matches and convincing them to give away matchbooks to their customers for free. Among the first companies to order advertising matchbooks were Pabst beer (from which Traute got his first order for 10 million matchbooks), American Tobacco Company and Wrigley’s Chewing Gum. Soon enough everyone followed suit, and matchbooks quickly became a cool way for businesses to advertise themselves to a wide audience due to their easy distribution, low cost, and portable nature.

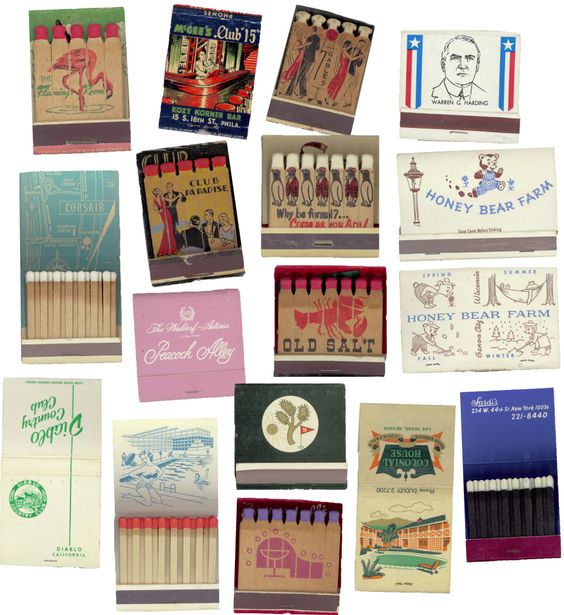

In the 1930s, the design of matchbooks changed again with the introduction of the “fold-over” style. This design featured a fold-over cover that protected the match stems from outside elements and made them easier to carry, also allowing for larger and more dazzling advertisements on the cover. The design of matchbooks evolved over the years as the demand grew, resulting into new materials and production methods being used and increasingly sophisticated and creative matches featuring bold colors and eye-catching graphics and slogans printed on both match covers and match stems. Lion Match Company, a smaller competitor to match giant Diamond, decided around 1935 to take matchbook advertising up a notch by introducing and trademarking the concept of feature matchbooks, which had advertising art on their covers as well as the match stems themselves. Despite Lion’s trademark, its original idea was thoroughly copied (today, feature-type matches are in fact among the hottest collectible items on the matchbook market).

During World War II, matchbooks became an important part of the war effort as well as a useful device for soldiers to light cigarettes and campfires. The U.S. government printed more durable and reliable matchbooks with patriotic messages and images, and soldiers were encouraged to distribute them to locals in foreign countries as a way to promote American ideals. General Douglas MacArthur even had matchbooks bearing the words “I shall return” dropped behind enemy lines in the Philippines.

Mendelson Opera Company matchbook

US WW2 War Bonds matches

Feature Matchbook

After the war, matchbooks continued to be favored by businesses and consumers alike and matchbook collecting became a popular hobby, with enthusiasts seeking out rare and unique designs to add to their collections. By the 1940s, it was estimated that more than one million Americans had become phillumenists—aka lovers of light, from Greek Phil- [Loving] + Latin Lumen- [Light]—and included people who had a shoe box or fish bowl filled with packs of matches from local stores and restaurants, to more serious collectors with matchbook covers organized in hundreds of different topics.

Thanks to the rise of graphic design as an art form in the 1950s and 1960s, matchbooks became a commercial advertising medium for bars, restaurants, and other businesses. Many establishments would print their names, logos, and addresses on matchbooks and leave them on tables for customers to take home as free souvenirs. This practice continued for several decades, with matchbooks remaining a common sight in bars and restaurants until the advent of smoking bans in the early 2000s and the rise of disposable lighters. One last change was made to the matchbook design because in 1973 a federal regulation mandated that the strikers be moved from the front of the matchbook to the back.

Today, matchbooks have begun to regain some of their traction as a retro advertising item, particularly in high-end restaurants, although they are much less common than they once were. With the rise of digital advertising and the decline of smoking, matchbooks have unfortunately lost some of their status, but they nevertheless remain an enduring symbol of American culture.

Collection of vintage matchbooks

Early 1900s front cover striker vs. 1973 back cover striker